Valentine’s Day has traditionally been a holiday for couples, an observance set aside for parents to give each other a special token of their love buy why not give you a present for yourself at Gainesville Coins you can have plenty of gold, silver and much more to start a beautiful collection.

Valentine’s Day has traditionally been a holiday for couples, an observance set aside for parents to give each other a special token of their love buy why not give you a present for yourself at Gainesville Coins you can have plenty of gold, silver and much more to start a beautiful collection.

Bouquets of flowers, boxes of chocolate, candy hearts and cards with arrow-wielding cupids come to mind. Aside from giving gifts, the thegirlfriendactivationsystem.com discusses more ways to make someone feel special during Valentine’s Day.

What doesn’t readily come to mind, but perhaps should, are neurons deep within the brain branching out between brain cells, cementing memories — both conscious and subconscious — to create a child’s knowing of love.

We ask you to give just $5 for Attachment Parenting International’s “Spread the Love” campaign. Each donor will receive a free API Teleseminar recording as our gift.

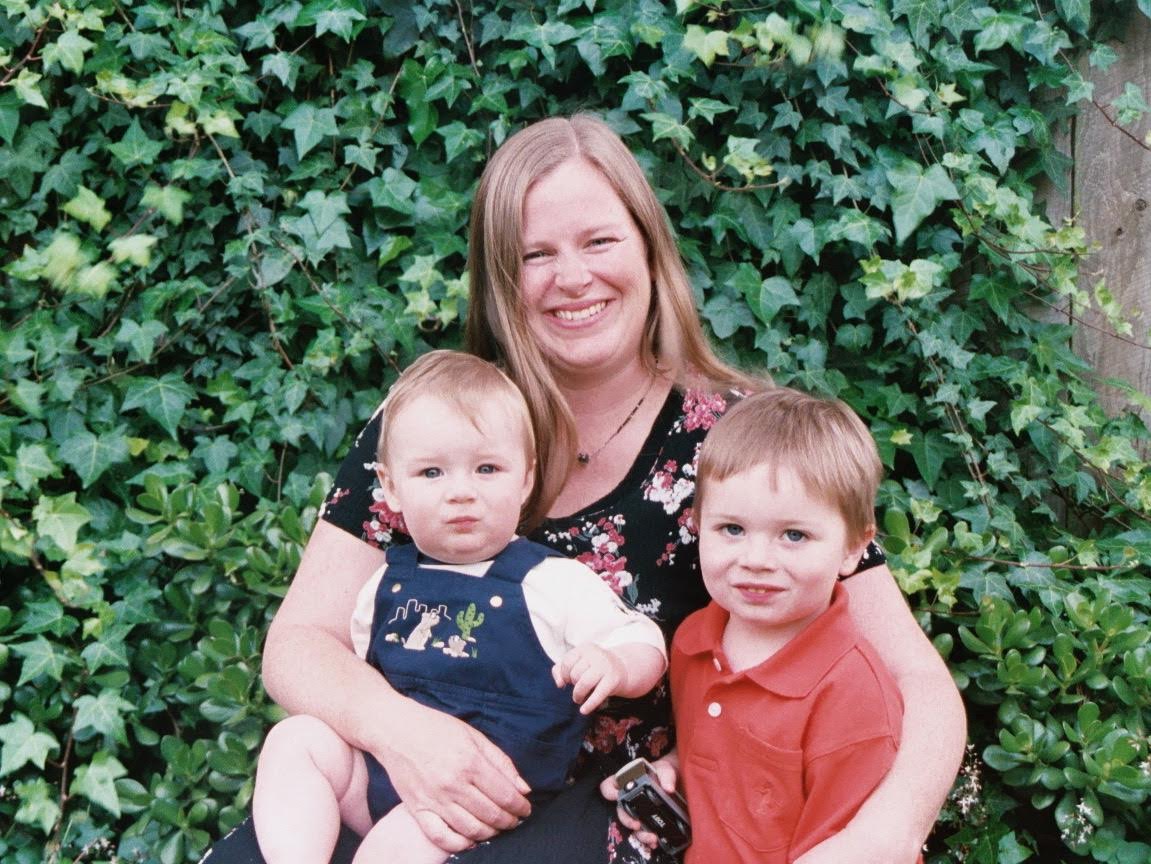

We may not think of this when we first discover Attachment Parenting. As parents expecting our first baby, or in the midst of that first year of our child’s life, or in the throes of toddler’s emotions, our understanding of Attachment Parenting is set on a more near-sighted goal: How do I as a parent, in this moment…prepare for pregnancy, birth and parenting…feed with love and respect…respond with sensitivity…use nurturing touch…ensure safe sleep, physically and emotionally…provide consistent, loving care…practice positive discipline…strive for balance in our family and personal lives?

In other words, when we are young in our own parenting journeys — and especially with infants and young children — our focus in Attachment Parenting is in the here and now. Attachment Parenting International’s Eight Principles of Parenting guide us to choose parenting behaviors that lead to more peaceful, compassionate, trusting, empathic and joyful relationships with our children. And in return, while it may be challenging at times to go against the cultural grain, we are ultimately rewarded with secure attachments to our children.

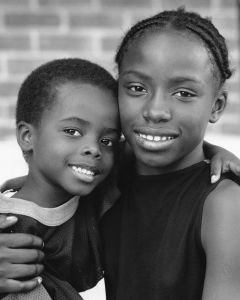

As our children grow older, and especially as we mature in our parenting journey, we begin to see the long-range possibilities of Attachment Parenting. We still enjoy the secure attachments within our families, and we still have challenges to overcome through our child’s development, but it gets easier to see beyond the day-to-day challenges of navigating what was once, to us, a new approach to parenting. We begin to be able to see Attachment Parenting as not only having positive consequences in our families but also our communities. What would it be like if all families practiced Attachment Parenting, if all children were able to grow up with a secure attachment to their parents? What would it be like for our communities if an entire generation grew up in peaceful, compassionate, trusting, empathic and joyful home environments?

I wonder, from time to time, what the dating scene will be like when my children are at the age of searching for a spouse. Who will they marry? What will their spouse’s values be? Will it be in line with what they’ve grown into through our Attachment Parenting home?

My children’s brains are being wired for peace, compassion, trust, empathy and joy. As so many of their peers, they like to play “House,” each taking the role of a family member, sometimes a parent and sometimes a child. Their play reflects how our family works. My 8-year-old daughter recently shared her concern about how other girls in her class play “House” while at school:

“I don’t understand why parents spank or ground their kids,” she said.

“Do you think there’s a better way for them to teach their kids?” I asked.

“Yeah, just talk to them,” she said. After a moment, she added, “And be sure not to do whatever you don’t want your child to do, yourself.”

Of course, positive discipline is more complicated than this. It folds in to the remaining of API’s Eight Principles of Parenting to create a certain home environment for positive discipline to work.

So, it’s not so easy to tell parents to stop spanking their kids or to stop having their babies cry-it-out or to be mindful of what childcare provider they choose or any other parenting behavior that does not closely align with Attachment Parenting. This is why it can be difficult for some parents to fully embrace Attachment Parenting. Attachment Parenting is a lifestyle that encompasses the goals of “raising secure, joyful, and empathic children,” as per API’s mission.

The second half of our mission is to support parents “in order to strengthen families and create a more compassionate world.”

API is in the love business. Volunteers around the world are working everyday on programs, locally and online, to educate and support parents in raising children whose brain neurons are forming each child’s reality of love. We ultimately want to see every child grow with the understanding that love is secure, peaceful, joyful, compassionate, trusting and empathic.

We want to banish parenting practices that raise children who grow up to become adults with an understanding of love as insecure — as a scientifically estimated 40% of the general population does — resulting in future parents who then struggle with trust and commitment, anger and fear, and possibly low self-esteem, poor coping skills, anxiety, depression or an insatiable fear of being abandoned.

Investing in API’s mission is an opportunity to not only ensure that programs and resources are available for you and your family, but also for the families in your community, state, nation and world — with the goal of not only love-centered, peaceful relationships at home but also in your child’s future adult home as well.

Celebrate Valentine’s Day this year by investing in your child’s future through our “Spread the Love” campaign and receive a free API Teleseminar recording in return for your generosity.

We are working toward a day when Attachment Parenting won’t need a label — it will just be parenting.

We are working toward a day when Attachment Parenting won’t need a label — it will just be parenting.Please consider donating $5 to API’s Spread the Love campaign.