Editor’s note: Attachment Parenting International hopes you enjoy this throwback Thursday post, originally published August 7, 2015. It remains a great example of breastfeeding as part of sustainable development, the theme of World Breastfeeding Week this year:

It is often noted that part of what makes breastfeeding so challenging at times is that in our Western culture, we just don’t see breastfeeding happening on a regular basis.

Nursing in public is still a rare occurrence relatively, especially without a nursing cover. Breastfeeding mothers are still getting kicked out of restaurants and stores. A photo of a breastfeeding baby with more of the breast exposed than a tidbit between folds of fabric can result in an entire Facebook page being shut down. Children are still encouraged to feed their dolls with a bottle, rather than at the breast, in public places like childcare centers and preschool. Working mothers, at many places of employment, continue to be directed to broom closets and bathrooms to pump…if they are allowed adequate pump breaks at all. The working and breastfeeding law doesn’t cover everyone!

Even with all the advances our medical community has made in promoting and supporting breastfeeding, our culture remains woefully behind in some ways. What shame there is in strangers’ claims of indecency!

In May of 2015, I attended a portion of the Standing Bear Symposium in Lincoln, Nebraska, USA, to hear Camie Jae Goldhammer, MSW, LICSW, IBCLC, present “Mitakuye Oyasin: Health and Healing through Motherhood.”

In May of 2015, I attended a portion of the Standing Bear Symposium in Lincoln, Nebraska, USA, to hear Camie Jae Goldhammer, MSW, LICSW, IBCLC, present “Mitakuye Oyasin: Health and Healing through Motherhood.”

Camie is a clinical social worker and lactation consultant, the founder and chair of the Native American Breastfeeding Coalition of Washington, a founding member of the Collaborative for Breastfeeding Action and Justice, and a member of the Native American Women’s Dialogue on Infant Mortality.

As a Native American herself — Sisseton-Wahpeton — she is intimately aware of the challenges of breastfeeding women among Native Americans. It helps put non-Native American cultural challenges surrounding breastfeeding into perspective and can give us understanding of why culture can seem to be so slow to change on the view of breastfeeding. Let’s look at the very critical factor of historical trauma.

What is Historical Trauma?

We understand what trauma is: something horrific that happened, that has lasting, often debilitating, effects collectively known as Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Symptoms can include:

- Flashbacks

- Disturbing dreams of the traumatic event

- Emotional distress

- Avoidance of places, activities or people that remind of the traumatic event

- Becoming emotionally numb or inability to feel happiness

- Negativity toward self or others

- Amnesia about the traumatic event

- Difficulty in close relationships

- Irritability and aggression

- High anxiety, particularly a feeling to always be on guard for danger

- A sense of overwhelming guilt or shame; and others.

Historical trauma is when the same traumatic event happens to an entire generation of people. Because it happened to the entire generation, there was no guidance within that generation as to how to heal from the trauma so that the PTSD behavior is transferred inter-generationally through the the parents’ thinking and behavior. And the same PTSD behavior continues to be passed down through the family tree, when healing has not occurred, with the trauma showing up generations later in certain stereotypical mannerisms attributed to that particular culture.

Camie shared an example of the Jewish people, in whom traits like high anxiety, overprotectiveness, and extreme frugality are seen as the stereotypical traits of this culture. These traits are also documented byproducts of the Holocaust among survivors. Without knowing it, Holocaust survivors passed these PTSD behaviors as family values to their children in how they coped with their trauma. And their children passed them to their children as part of their lifestyle, and so on and so on…to a point in their family tree where people with no firsthand exposure to the Holocaust continue to display the same PTSD-like behavior generations later.

That’s historical trauma.

Camie gave other examples of culture suffering from historical trauma: the peoples of Cambodia, Russia and India as well as the Native Americans.

How Does Historical Trauma Relate to Breastfeeding?

Among Native Americans living on a reservation, breastfeeding rates are extremely low. Statistics depend on the exact location, but here are the breastfeeding hurdles common to most reservation, to give you the big picture:

- High teen pregnancy rates

- No local obstetrician services so most women do not receive any prenatal care and therefore no breastfeeding education

- Very few local lactation specialists, especially among peers

- Low pump-at-work support from employers

- Access to free formula through federal nutrition programs.

But these are surface symptoms of the real problem: The historical trauma of generations of oppression of native parenting, including breastfeeding.

Camie detailed 6 phases of unresolved grief through the generations of Native Americans:

- Colonization by white people – Besides introducing disease and alcohol, there was much death among native peoples at this time, including genocide.

- Economic competition – Native peoples began losing their ability to be self-sufficient, beginning to rely on trade with the white people for supplies.

- Invasion and war – White people begin exterminating native peoples, and those who don’t die become refugees.

- Subjugation through reservations – Native peoples are confined to locations often very different than their homelands and are forced to depend on their oppressors.

- Boarding schools – Native children are forcibly removed from their birth families to be educated in a foreign religion and customs, and were severely physically punished as they were forced to conform. This generation is called the “lost generation,” as 70% of native children were taken from their families and culture.

- Forced out of reservations – After the boarding schools were closed, white people resorted to forcing adolescent native youth to live off the reservations in what they called “red ghettos” in U.S. cities, away from their families and culture as an attempt to give them a better life than on the reservations.

From generation to generation — because each of these traumas were happening to all the peoples of each generation — there have been terrible, widespread effects on Native Americans, particularly those who live on reservations. The poorest areas in the United States — some without running water, even — are located on reservations. The generational response to this succession of historical trauma has resulted in:

- Clinical PTSD

- Depression

- Unidentified/unsettled emotional trauma, which is displayed through mental illness, anxiety disorders and anger issues

- High mortality rates, including suicide and murder

- High rates of alcoholism, domestic violence and child abuse.

What’s more, there is also a prevalent discouragement from bettering oneself, because it feels like a betrayal of past generations that suffered and lost so much.

Women, specifically, have lost confidence in their bodies and their ability to mother, and have learned to defer their decision-making potential to a male-dominated culture. Native women see menstruation, childbirth and breastfeeding as shameful. The generational wounds of native women include:

- Loss of empowerment in the mother role

- Devaluation of native parenting, which embodies a feeling that parenting is a sacred responsibility, that children have wisdom, that children are the future of the Nation and therefore need to be raised with a sense of incredible value.

Because breastfeeding equals maternal power, how do we expect a native woman to breastfeed if this — disempowerment and devaluation — is what she feels like?

Breastfeeding Can Heal Generations

In her private practice, Camie works off the 7th Principle, meaning that whatever a person’s choices, that person’s actions have a ripple effect to the next 7 generations. Camie believes that breastfeeding can change everything…in how we view children, mothers, families, parenting, community, generations and humankind overall.

Breastfeeding is a statement: that a mother, family, community and culture is willing to give the best to their children. Breastfeeding is a protest to a culture that devalues children and families.

Breastfeeding is an act of power. The top causes of infant mortality among native peoples are Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS), respiratory infection and influenza. The risk of each can be lowered through breastfeeding.

Camie’s great-great-great-grandmother was the last generation since Camie to breastfeed her children. This relative had 5 sons and all were forcibly removed one day by the U.S. government to grow up in boarding schools. How they each coped with this separation and loss of culture rippled through the generations until it seemed that the knowledge and art of breastfeeding, and mothering, had been lost.

But it was not lost on Camie. She breastfed her oldest for 4 years, and is currently breastfeeding her 3 1/2 year old. Camie seemed to be born with the desire to always question the status quo.

Camie talked about how trauma, historical or individual, will always be passed down through each generation until someone is able to step back and question why their family does things a certain way and is willing to look deeply into that family’s trauma to heal.

Cultural Changes Helping Mothers to Breastfeed, Too

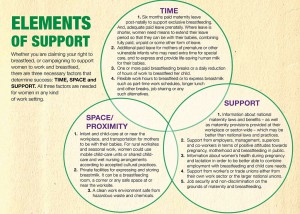

The culture has changed its attitude toward native mothers, too. Western culture has worked to help heal the emotional wounds of Native Americans, though there is still so much work to do. Camie identified these needs among native mothers to improve breastfeeding rates, which are not so different than what we all — Native American or not — need from Western society:

- Support from peers, especially those trained as lactation specialists

- Prenatal education specific to breastfeeding and emotional barriers, such as not wanting baby to be physically close, a sign of unidentified trauma

- Targeted breastfeeding education to mother’s support persons, especially grandmothers, sisters, aunts and other women who the mother relies on for emotional support.

The Strength of a Breastfeeding Mother

After Camie’s talk ended, several native mothers shared their amazing stories of breastfeeding success against all odds. One woman told of how her boyfriend threatened to beat her if she continued to breastfeed past 6 months, so she would sneak the baby into the shower and other out-of-the-way places in the home to breastfeed until she was able to get out of that abusive relationship. It took months, but she is still breastfeeding — now tandem-nursing that older child alongside a newborn.

Another mom told of how she gave birth to her first child when she was still a high school student, but the school wouldn’t allow her to pump, so she hand-expressed breastmilk in the school bathroom. She talked about how she would leak breastmilk during the day and would have to put up with negative comments from peers and teachers about that.

The undercurrent through both of these and other stories is women finding their power as mothers, reclaiming their confidence as women.

White American Mothers, Historical Trauma and Breastfeeding

While Camie’s presentation was directly related to the Native America culture and breastfeeding, I think it can be easily applied to any population of women living in a culture struggling with supporting breastfeeding.

While Camie’s presentation was directly related to the Native America culture and breastfeeding, I think it can be easily applied to any population of women living in a culture struggling with supporting breastfeeding.

I am not Native American, but as the typical white American, I can look back in my family tree and see the history of breastfeeding is much the same as it was for my white American friends: After World War II, formula really took hold as the “best” way to feed babies, so much that the medical community was recommending formula over breastfeeding. The only families that were breastfeeding for any length of time typically were the poorest families, those who couldn’t afford the cost of formula. Formula also gave mothers the choice to be able to work outside the home, a freedom of choice that coincided with the feminism movement. At the same time, however, our white American mothers were losing the significance of breastfeeding — that is central to not only infant and child health, but also the mother-infant bond and the beginnings of secure family attachments.

I was discouraged as a new mother to my first child, by a nurse at the hospital, to exclusively pump unless I didn’t qualify for free formula through the federal nutrition program. I chose to listen to my instinct instead: Breastmilk was something I could give to my baby that no one else could.

Breastfeeding empowered me to embrace the role of mother, despite strong discouragement at times from Western culture. For me, as a white American who is overcoming historical trauma placed on generations of white American mothers who were discouraged from breastfeeding and Attachment Parenting, breastfeeding is a statement: that I, as the mother, know what was best for me and my children.