I don’t know how Bob got the name. Something about Bob wanting to break up with Ben, my son. I said it in jest and it just took. During the times I didn’t want to breastfeed, somewhere between a meltdown and bad day, I would say to myself or maybe even out loud, “Ben — Bob wants to break-up with you.” Some days I will be honest, I hated breastfeeding. I wanted to slip out the back Jack, make a new plan, Stan…” but I continued breastfeeding because I finally got to a place where I trusted my instinct and my choices. I knew that Ben would decide when it was time to end breastfeeding. I dropped the worry. I dropped the internal criticism. I just followed my heart.

I had a hard time with breastfeeding at first. It was awful. Nipple scabs. Bloody nipples. Pain. PAIN. And more pain. I remember being determined to make it work, but it was awful. Those first weeks of breastfeeding were some form of torture. When my son latched on, it was so painful. I felt like my nipples were rocks with the sensitivity of an ocean full of neurotransmitters right to my breasts and nipples.

We got through it. I called La Leche League. I called friends. I called my mom. But I felt like a failure. Nobody had told me it would be this hard. Nobody mentioned my nipples would have scabs and bleed. My husband came home with four different bags of candy on a particularly hard day. In his hands, he held two bags of candy, creams, Soothies (gel like cooling pads you place over your nipples) — and kindness that can not be measured. He was also draped in some sort of patience suit — he had to have been because I was not at my best those early weeks of breastfeeding. He hugged me. He kissed me. He knew this was something he could not empathize with, but he did offer sympathy. I devoured the bags of candy. Then I put on the cream and placed the Soothies over my breasts. I had a sense of relief for about fifteen minutes, until the next time my son wanted to breastfeed.

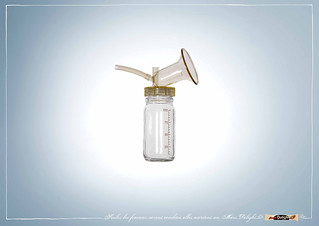

I did it all wrong. I had no clue what I was doing. I had never heard of Attachment Parenting. The lactation consultant that the hospital sent over to do a check-in at the home made a ten minute stop at my house. I stumbled to the door and managed to say hello. She gave me a hand held breast pump, quickly explained how to use it and sat with me on the couch for five minutes watching me breastfeed. I was desperate for information.

“Is this the right position?” I asked impatiently.

“Yes,” she offered.

“Are you sure?” I was so desperate — so clueless. So hormonal. OK — I was crazy. I hadn’t slept in a week. As they say in the South, I was a hot mess!

“Is this the easiest way to breastfeed?” I asked, hoping to dig an answer out of her.

“Yes,” she offered again, this time checking something off on her clipboard.

“Can you please show me an easier way to breastfeed? I feel like I am doing it wrong.”

“You’re doing it right.”

She showed me the football hold, telling me this may be easier for me. As my son fumbled in my arms, I felt foreign in my own body. I felt clumsy, unsure, and awful.

Why does it feel like I am doing it wrong? Why does it hurt so much? I wanted to ask.

She left my house. I wanted to scream at her, “Get back over here. We’re not done here. In fact we have not even started. Cancel all your appointments — you are mine for the afternoon.” But I said goodbye and she went on to the next home, the next mom, who was probably just as afraid and insecure as I was.

I called La Leache League immediately after she left and was hysterical, gasping into the phone. I think I thought they too were the enemy and asked them a slue of questions, ending each one with, “You guys probably think I am doing it wrong.”

For some reason they were the enemy. My own breasts were the enemy. The nipples scabs were the shrapnel wounds. My own son, the heavy artillery.

So, what did work? How did we get to a happy healthy breastfeeding relationship? I worked at it. I suffered through the pain. I called my friend, Debra — who nursed all her children until they were three. She sat with me while I nursed. She watched me. She assured me I was doing it right. I finally allowed myself to believe her. She was very honest. She told me it would hurt until Ben and I got used to each other. She said it took time. It was something new for the both of us. He was learning how to breastfeed, just as much as I was learning to breastfeed.

I went to a local nursing mothers support group. We sat in a circle with our newborn babies — staring at each other and our babies. I broke the ice by saying, “My boobs feel like they are going to explode.” Then we all exchanged stories, fears, laughter, tears. A good friend of mine who was in my Lamaze class suggested I switch my nursing pillow. I ditched the one I was using and took her suggestion.

During the first few weeks, I used to set the alarm for every three hours, then take my Moses Basket filled with pillows, blankets, my safety pin (to remind me where I had nursed last), and the notebook where I wrote down every detail of how long my son nursed for. The basket held my pillows, the Boppy, and the nipple cream; it held my insecurity. I would slather on the cream, turn on the light to the living room, and arrange my pillows so I could start nursing. It was three AM might I add. And I insisted on turning on the living room light. I was so rigid. I was unable to let myself flow in this breastfeeding relationship. It had to be by the book, but I had no book to follow. I should have read more. I should have practiced. I should have…I should have…kept ringing in my ears. I had never heard of Attachment Parenting. I was determined to do it by the book. I even called a friend to ask her about using a pacifier. “I don’t want him to get nipple confusion.” We had an awkward conversation, filled with frantic questions, but answers seemed so far away. I felt alone and lost.

My friend, Debra, who came over and supported me with her smiles, tender looks, and approving nods, just said simply, “Why don’t you nurse him in your bed? Let’s try it. It is much easier lying down.”

I said, “No way, he is NOT coming into our bed. I might roll over him and crush him.”

She just smiled. I knew she knew something I didn’t. I was so determined to use the football hold and the across my chest hold.

Organically, Ben found his way into our bed and we co-slept as a family. I did not roll over him; I did not crush him. In fact, my husband commented on how protective I was of him when we slept, with my arm arching over him like a rainbow.

The truth is, I had to go back to work when my son was four months old; I was exhausted waking up in the middle of the night. I stopped setting my alarm every three hours and learned to trust the fact he would cry when he needed to be fed. He did. We figured it out. Along the way, I learned to trust my own instincts. I became the gardener in our organic garden of mother and son.

We learned together and found our way.

I told my friend, Debra, that there was no way my son would reference my breast by name. There was no way.

She told me a funny story about her three year old having a temper tantrum over wanting Ninny. Her daughter was eating spaghetti by the handful in her high chair. Messy red clumps of sauce on the floor, on the chair, on her hair. Her daughter called out, “Ninny, Ninny, Ninny. I want Ninny.”

Well, now that my son is two and half, he often would ask for the breast by name. In this case, “Bob.” He would say, “Bob inside. Can I have milk inside Bob?” Bob became his comfort, his nurturer, his friend. We decided that we would stop breastfeeding when Ben was ready. Ben has recently stopped. He sometimes lays his head on my breast, smiling and patting Bob.

Hello parents! The cover was risky but a brilliant hook by Time Magazine to attract readers, and they achieved their goal. The writer, Kate Pickert, herself a new mother and one of Time’s most diligent writers, sincerely wanted to increase awareness of the Sears’ family contribution to parenting and family health. She lived with our family for two days, followed me in the office, and spent hours with me on the phone in an attempt to be factual. While the cover photo is not what I or even cover-mom Jamie would have chosen, it accomplished the magazine’s purpose. And, as some attachment dads observed, finally a magazine displays a woman’s breast for the real purpose for which they were designed – to nurture a child, not to sell cars and beer. Cover-mom Jamie is a super-nice person and highly-educated in anthropology, nutrition and theology. I enjoyed the several hours I spent with her family and her kids shined with the social effects of attachment parenting.

Hello parents! The cover was risky but a brilliant hook by Time Magazine to attract readers, and they achieved their goal. The writer, Kate Pickert, herself a new mother and one of Time’s most diligent writers, sincerely wanted to increase awareness of the Sears’ family contribution to parenting and family health. She lived with our family for two days, followed me in the office, and spent hours with me on the phone in an attempt to be factual. While the cover photo is not what I or even cover-mom Jamie would have chosen, it accomplished the magazine’s purpose. And, as some attachment dads observed, finally a magazine displays a woman’s breast for the real purpose for which they were designed – to nurture a child, not to sell cars and beer. Cover-mom Jamie is a super-nice person and highly-educated in anthropology, nutrition and theology. I enjoyed the several hours I spent with her family and her kids shined with the social effects of attachment parenting.