I recently exchanged e-mails with one of my former students about the perennial question concerning human nature: Are humans good or bad?

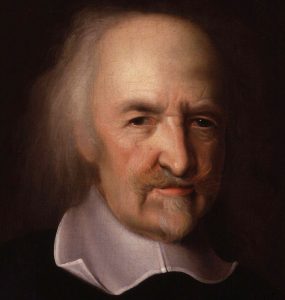

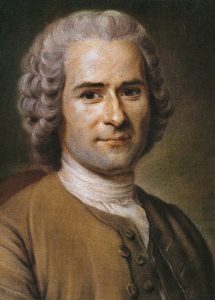

This question continues to fascinate us. When I lecture about human nature to my students, I like to frame the debate by pitting Thomas Hobbes against Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) was an English philosopher and the author of the book Leviathan. Famously, Hobbes declared that primitive human life was “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.”

Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) was an English philosopher and the author of the book Leviathan. Famously, Hobbes declared that primitive human life was “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.”

I use Hobbes to illustrate a pessimistic view of natural man. That is, as illustrated by his famous summation, Hobbes felt that the natural state of man was bestial. According to Hobbes, therefore, it is civilization that steps in and rescues humanity from our primal depravity. In this view, human nature is a nasty thing that human culture rescues. In Hobbes’ view, being civilized is good and being a savage is bad.

Contrast that with the view of Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778), the Enlightenment philosopher whose book The Social Contract influenced the French Revolution: “Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains.”

Contrast that with the view of Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778), the Enlightenment philosopher whose book The Social Contract influenced the French Revolution: “Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains.”

In contrast to Hobbes, Rousseau declared that humans in earlier times were “noble savages.” According to Rousseau, humans are naturally and innately good, and it is civilization that turns man into a “beast.” Consequently, Rousseau argued that modern man should seek to restore the conditions of our lost Eden and live a more natural, rather than technological, life.

To summarize, we can create a quick schematic contrast of Hobbes and Rousseau:

- Hobbes — Human Nature = Bad, Civilization = Good

- Rousseau — Human Nature = Good, Civilization = Bad

For Hobbes, civilization saves us from ourselves. Without it, we would regress to a beast-like state. For Rousseau, civilization is killing us. For Rousseau, the goal is to reclaim a more natural existence.

So, who is right?

Unfortunately, by this point in my lecture, only a about two students are awake. So, to show them that this question is actually of practical and not just academic interest, I like to ask the following question: Are you planning to breastfeed your baby?

This question gets the girls awake, for obvious reasons. It gets the boys awake because the word “breast” was used. Human nature, good or bad, can at times be remarkably predictable.

I bring up parenting in the conversation about Hobbes and Rousseau, because it is in parenting where we tend to reveal if we vote with Hobbes or Rousseau.

For example, Hobbesian parents tend to think that a child’s nature is unruly, undisciplined, and selfish — not in an evil sort of way, more of a benign “they don’t know any better.” Thus, these parents tend to emphasize training and structure.

Rousseauian parents tend to think that a child’s nature is innocence and goodness. These parents tend to de-emphasize structure in the child’s environment.

Here are some more possible locations of contrast:

- Painkillers during delivery — Hobbesian parents more likely to use painkillers; Rousseauian parents more likely not to use painkillers.

- Feeding — Hobbesian parents more likely to bottle-feed; Rousseauian parents more likely to breastfeed.

- Feeding Times — Hobbesian parents more likely to feed on a schedule; Rousseauian parents more likely to feed on demand.

- Discipline — Hobbesian parents more likely to spank; Rousseauian parents more likely not to spank.

- Sleeping — Hobbesian parents more likely to allow child to cry in crib until asleep; Rousseauian parents more likely to hold child until asleep.

Now, I’m not suggesting this as some kind of rigorous, diagnostic classification. I’m mostly trying to illustrate a point: Whether we like discussing human nature or not, we are all working with a theory of human nature and that theory of human nature has practical consequences. For example, when parenting, some of us go “natural.” Others are more “technological” — painkillers, formula, behavioral parenting strategies.

And parenting is hardly the only place where we see these differences. We see Hobbesian and Rousseauian contrasts in how we choose to eat, how we choose to use medicine, and how we feel about city life — to name a few things.

Hobbes and Rousseau are still with us. And we, in the choices we make, keep their debate alive.

*Reprinted with permission from Richard Beck, PhD. The original article is published on Experimental Theology.

**Philosophers’ photos from Wikimedia commons.