Category: Feed with Love and Respect

The AP challenge: Parent with kindness, respect & dignity

A deep sense of gratitude

Is human nature inherently good or bad? And does this predict what type of parent you will be?

I recently exchanged e-mails with one of my former students about the perennial question concerning human nature: Are humans good or bad?

This question continues to fascinate us. When I lecture about human nature to my students, I like to frame the debate by pitting Thomas Hobbes against Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) was an English philosopher and the author of the book Leviathan. Famously, Hobbes declared that primitive human life was “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.”

Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) was an English philosopher and the author of the book Leviathan. Famously, Hobbes declared that primitive human life was “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.”

I use Hobbes to illustrate a pessimistic view of natural man. That is, as illustrated by his famous summation, Hobbes felt that the natural state of man was bestial. According to Hobbes, therefore, it is civilization that steps in and rescues humanity from our primal depravity. In this view, human nature is a nasty thing that human culture rescues. In Hobbes’ view, being civilized is good and being a savage is bad.

Contrast that with the view of Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778), the Enlightenment philosopher whose book The Social Contract influenced the French Revolution: “Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains.”

Contrast that with the view of Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778), the Enlightenment philosopher whose book The Social Contract influenced the French Revolution: “Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains.”

In contrast to Hobbes, Rousseau declared that humans in earlier times were “noble savages.” According to Rousseau, humans are naturally and innately good, and it is civilization that turns man into a “beast.” Consequently, Rousseau argued that modern man should seek to restore the conditions of our lost Eden and live a more natural, rather than technological, life.

To summarize, we can create a quick schematic contrast of Hobbes and Rousseau:

- Hobbes — Human Nature = Bad, Civilization = Good

- Rousseau — Human Nature = Good, Civilization = Bad

For Hobbes, civilization saves us from ourselves. Without it, we would regress to a beast-like state. For Rousseau, civilization is killing us. For Rousseau, the goal is to reclaim a more natural existence.

So, who is right?

Unfortunately, by this point in my lecture, only a about two students are awake. So, to show them that this question is actually of practical and not just academic interest, I like to ask the following question: Are you planning to breastfeed your baby?

This question gets the girls awake, for obvious reasons. It gets the boys awake because the word “breast” was used. Human nature, good or bad, can at times be remarkably predictable.

I bring up parenting in the conversation about Hobbes and Rousseau, because it is in parenting where we tend to reveal if we vote with Hobbes or Rousseau.

For example, Hobbesian parents tend to think that a child’s nature is unruly, undisciplined, and selfish — not in an evil sort of way, more of a benign “they don’t know any better.” Thus, these parents tend to emphasize training and structure.

Rousseauian parents tend to think that a child’s nature is innocence and goodness. These parents tend to de-emphasize structure in the child’s environment.

Here are some more possible locations of contrast:

- Painkillers during delivery — Hobbesian parents more likely to use painkillers; Rousseauian parents more likely not to use painkillers.

- Feeding — Hobbesian parents more likely to bottle-feed; Rousseauian parents more likely to breastfeed.

- Feeding Times — Hobbesian parents more likely to feed on a schedule; Rousseauian parents more likely to feed on demand.

- Discipline — Hobbesian parents more likely to spank; Rousseauian parents more likely not to spank.

- Sleeping — Hobbesian parents more likely to allow child to cry in crib until asleep; Rousseauian parents more likely to hold child until asleep.

Now, I’m not suggesting this as some kind of rigorous, diagnostic classification. I’m mostly trying to illustrate a point: Whether we like discussing human nature or not, we are all working with a theory of human nature and that theory of human nature has practical consequences. For example, when parenting, some of us go “natural.” Others are more “technological” — painkillers, formula, behavioral parenting strategies.

And parenting is hardly the only place where we see these differences. We see Hobbesian and Rousseauian contrasts in how we choose to eat, how we choose to use medicine, and how we feel about city life — to name a few things.

Hobbes and Rousseau are still with us. And we, in the choices we make, keep their debate alive.

*Reprinted with permission from Richard Beck, PhD. The original article is published on Experimental Theology.

**Philosophers’ photos from Wikimedia commons.

Have guilt? Find your parenting anchor point

Guilt seems to be inherent in parenting. It doesn’t really matter how you parent, it’s so tempting to compare ourselves to others and how they are relating to and raising up their children.

Guilt seems to be inherent in parenting. It doesn’t really matter how you parent, it’s so tempting to compare ourselves to others and how they are relating to and raising up their children.

As a working mother in a conservative area, I feel this tug of parenting guilt from time to time. A common scenario in the small, farming community where my family lives is for a mother to stay at home with her children when they are young and then get a job at the school when her youngest child enters kindergarten. It sounds like a great gig!

But that is not my choice. I did work, both from home and outside the home some days, when my children were small and continue to work year-round now that my children are in school. I love what I do and feel that I make a meaningful impact through my career. I know my stay-at-home friends don’t mean to, but sometimes I hear — whether real or perceived — overtones that what’s best for children in general is for the mother to stay at home full time, without a paycheck-yielding job.

I suspect my guilty feelings are largely perceived than actual. I trust that even if other mothers don’t agree with my career-oriented lifestyle, that they are mature enough to allow me the freedom to parent my way. Unfortunately, like all of us, I am sometimes the target of others wanting to pressure me into their way of looking at the world.

I am a stalwart proponent of informed choice. While I do believe that every child deserves to be raised in a home with secure, healthy family attachments, I know that my own “brand” of attachment parenting is not the “be all, end all.” We, all of us parents, make the best decisions at any one time with the knowledge, support, and resources we have available. Every family is unique, and even among families with the same values and goals, mannerisms and lifestyle will vary — because just as every individual is different, so is every family.

All children, all parents, all families — everyone deserves healthy, secure attachment bonds within their social groups. For parent-child relationships, API’s Eight Principles of Parenting provide 8 areas of family life, with a variety of ideas within each, as to how to form and strengthen attachment bonds within families. But that doesn’t mean we all do things the same way.

Like with nurturing touch, I didn’t do much babywearing but holding my baby and cuddling with my children is definitely my thing! Or with childbirth, I had an epidural, a cesarean, and a VBAC, and while my unmedicated birth experience definitely made it easier to bond with my newborn, the high-intervention births didn’t hinder what has turned out to be a very secure attachment with those children. I also have experience with both breastfeeding and bottle-nursing, cosleeping and crib use, and all kinds of childcare situations.

Parenting, like everything else, has different seasons. We have to change, almost constantly sometimes, it seems, to keep up with our growing infants and children — in how to match their development with our guidance and passing down of our family values, as well as renew techniques of maintaining warm, sensitive, and appropriate ways of interacting with, relating to, and staying attached with our ever-changing little ones as they mature into adolescents and finally fledged on their own.

Parenting, like everything else, has different seasons. We have to change, almost constantly sometimes, it seems, to keep up with our growing infants and children — in how to match their development with our guidance and passing down of our family values, as well as renew techniques of maintaining warm, sensitive, and appropriate ways of interacting with, relating to, and staying attached with our ever-changing little ones as they mature into adolescents and finally fledged on their own.

We are all on our own parenting journeys of exactly how we will do this in our individual family. But like all parents, since probably the beginning of history — since we are all unique and so are our children and our partners — are also learning “on the job.” There are no handbooks that apply to every situation.

My home library is full of books on family relationship theory, research, and advice. Yet, my personal approach to parenting is a mix that goes well beyond the bits and pieces of these books that I found helpful — among the bits and pieces that I feel don’t apply to my family but certainly they may apply to another family — and include bits and pieces of how I was raised, the lessons learned reflecting on years of parenting already behind me, thoughts from friends and family members, my instincts, the reality of unavoidable challenges, scientific studies, blogs and websites, parenting classes and support groups, teleseminars, conferences, and so much more.

We are all doing this: gathering information from the world within and around us to figure out the best way of parenting our children and nurturing our families. Because its learning-as-we-go, there are ample opportunities for doubt to creep in. When we are stumped by our child’s behavior, especially if we are trying something new — such as breastfeeding our baby rather than resort to formula — it’s easy to think that maybe we’re doing something wrong or not good enough.

Unresolved doubt can grow into guilt. “What if…?” may fill our heads, as we compare ourselves and our children and our families to others, when those other families are likely doing the same kind of comparison maybe even to yours.

I’d like to get away from the thought that guilt is somehow unnatural and shouldn’t be felt. There are whole books written on the topic of “mothering guilt,” and there is a lot of blame being thrown around toward specific parenting approaches. But guilt is a natural human emotion, something that comes out of normal social interaction. As social beings, we will naturally feel guilt if we engage in a behavior that we perceive to have compromised our own standards.

Guilt can be helpful in that it motivates us to do better — though if unchecked, guilt can definitely be unhealthy and lead to anxiety conditions. The absence of guilt in a person, however, can be just as unhealthy: A lack of this emotion is implicated in individuals with a high degree of psychopathy.

Regardless, guilt is an uncomfortable feeling and one that no one wants to be immersed in for long. Being emotionally uncomfortable, such as with guilt, can keep us from being free to parent how we want to, bogging us down into doubt and even despair, and preventing us from the joy we seek in our parent-child relationships.

The idea that certain parenting approaches create more guilt in parents than others is, I believe, unfounded. Rather, from what I have found in my experience of providing parent support in a variety of settings for more than a decade is that what creates guilt is fear — namely, fear for their child’s well-being. I have seen this in many parents, no matter their child-rearing approach — attachment parenting or no — and most often in new parents or in parents trying something new that they hope will create better results but, they realize, stepping out from the familiar carries risk and with that risk comes fear. So where does fear come from? From what I find, it’s often a lack of parent support.

Regardless of what child-rearing approach parents choose, its incredibly — crucially — important that they find support. API offers both online and local, in-person support through a variety of resources, though research finds that the most valuable support for parents is through in-person support groups — of which API has across the United States and around the world.

It’s so important to find like-minded parents who can offer their “been there, done that” stories, emotional scaffolding, and specific suggestions for when you feel confused as to what to do about your child’s behavior, or when you question whether this new thing you’re trying, like positive discipline instead of spanking, for example, is going to work out in the long term, or how exactly to keep those family attachment bonds strong as your children grow, or how to move forward when your family encounters challenging life circumstances.

Attempting to find support among parents who do not share the same approach to child-raising is like comparing apples to oranges, and the advice you receive is likely to deepen the sense of doubt being felt, and therefore create guilt — not to mention conflict with your personal values system, which creates its own set of uncomfortable emotions.

Attempting to find support among parents who do not share the same approach to child-raising is like comparing apples to oranges, and the advice you receive is likely to deepen the sense of doubt being felt, and therefore create guilt — not to mention conflict with your personal values system, which creates its own set of uncomfortable emotions.

All parents want to feel validated in their decisions, and even if they do not intentionally seek out support, unsolicited advice will come their way — from family, friends, pediatricians, teachers, strangers, and others. But without having that anchor in a group of like-minded parents to act as your sounding board, to help guide you to make parenting choices that are in line with your values, you may find yourself swaying with the advice like a bottle cork in the ocean tide.

It’s very difficult to get grounded in your self-confidence as a parent without an anchor point. I cannot overemphasize the value of parent support.

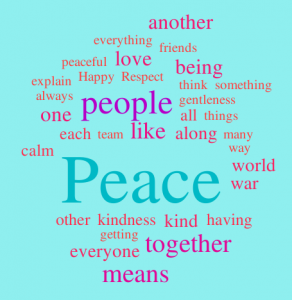

What is peace to children?

API hopes you have found AP Month 2016 to be enlightening and inspirational as we explored this year’s theme, “Nurturing Peace: Parenting for World Harmony.” On this last day of AP Month 2016, we bring you insight to what our children are internalizing as to what peace is:

API hopes you have found AP Month 2016 to be enlightening and inspirational as we explored this year’s theme, “Nurturing Peace: Parenting for World Harmony.” On this last day of AP Month 2016, we bring you insight to what our children are internalizing as to what peace is:

Emily, 8: “Calmness.”

Noemi, 8: “Peace means that everything is relaxing and calm.”

Emily, 10: “Quiet and relaxed.”

Violet, 10: “When people are calm, kind, peaceful, and respectful.”

Jacqueline, 7: “Love.”

Takumi, 7: “When I think of peace, I think of T.R.A.C.K.: Tolerance, Respect, Appreciate, Care, and Kindness. So if we have TRACK in heart, we can stay in peace.”

Zaiah, 10: “It is not war. It’s kindness. It’s being kind to each other. Peace is showing love to one another. Peace is having gratitude. Peace is love and gentleness.”

Remy, 14: “Peace to me means no child anywhere would know violence.”

Sophie, 5: “Peace means that I love my sisters.”

Rachel, 10: “Like not fighting, like what Martin Luther King, Jr., did with having people come together in peace, between different people. Like quietness and being calm.”

Thank you to Rachel, for suggesting this post for AP Month 2016. She is a 4th grader at Sandy Creek Public Schools in Clay County, Nebraska, USA. Contributions came from children around the world, thanks to the wide reach of the parents who volunteer with API.

Nathan, 5: “Not fighting. We should all work together as a team. No one, boy or girl, is better than another. We are all special.”

Camille, 18: “Peace is love, patience, truthfulness, kindness, and gentleness, and something we must achieve together.”

Luke, 10: “Peace is not war. It is peace. It is being kind to one another. It is sticking together, staying together as the world.”

Luke, 10: “Peace is not war. It is peace. It is being kind to one another. It is sticking together, staying together as the world.”

Ethan, 8: “Happy and the only way people can get along.”

Alexandra, 11: “Peace is something that is almost impossible. There are always fights, problems, and stress. Big things like wars and small things like bickering always happen. But every once in a while, the world may have a minute of peace.”

Shelly, 11: “Everyone getting along and respecting one another.”

Daniel, 14: “All nations and religions will be tolerant of one another.”

Anna, 8: “Peace means to get along with everyone no matter what they look like.”

Juliana, 13: “Peace is everyone working together and no war. People helping people.”

Brook, 10: “It means not fighting and being kind.”

Bennett, 9: “Peace means no terrorism, no war, and no murder.”

Harrison, 11: “Harmony.”

Oliver, 9: “Peace means that the people get together and have a good time, and get through the bad times, and have a bright and sunny and peaceful world.”

Samantha, 13: “Peace is hard to explain since it has many interpretations and definitions, as well as having peace in many shapes and forms. However, the best way to explain it is when people learn respect, tranquility, simplicity, and equality within everything.”

Miranda, 9: “People getting along and the world being a happy place for everyone. Everybody is friends and doesn’t hate each other ever.”

Coby, 11: “When people aren’t angry and people are friends.”

Luke, 14: “Rather than fight each other, orcs and humans team up.”

Hiroto, 3: “Peace? I like peace. Mama, what’s a peace? I like peace. Yes, I accomplished!”