Imagine you’ve just had done some dental implants in Chicago. Your deadened nerves make your mouth droop on one side. You’re drooling, but you don’t know you’re drooling because you can’t feel your face. Your tongue feels like it doesn’t quite fit in your mouth. For more tips, you can refer to this site.

And then, the phone rings. Someone’s calling about that job you’ve had your eye on, or the hard-to-reach medical billing department has just one more question to resolve the expensive mistake on your statement. You try to respond. You carefully coordinate your mouth muscles, but it’s useless. As much as you try to form words, they just don’t come out right. After a few tries, you start to sense frustration in the voice on the other end. The other person makes a snide comment before giving up and hanging up.

Imagine hiking in a new place, exploring as you go. You’ve just discovered the most fascinating artifact. You climb a few rocks to get a closer look. You’re able to reach it, touch it, marvel at it. Then suddenly, someone twice your size appears out of nowhere, pries it out of your fingers and hides it, for no apparent reason. He mumbles something in another language, and disappears.

Imagine dozing off after reading your child’s favorite book about giants. You start to dream about wandering around a strange, large world built for giants. The stairs come to your waist, you can barely peer over the dining table, and your drinking glass is the size and weight of a landscape planter. You spend your day trying to navigate this world, only to find that you’re constantly falling, running into things, breaking things, and spilling things.

Now, imagine these annoying obstacles are here to stay for a while. And imagine every time you make a mistake, a policeman pops out of nowhere, starts barking through a bullhorn and whacks you on the rear with a billy club.

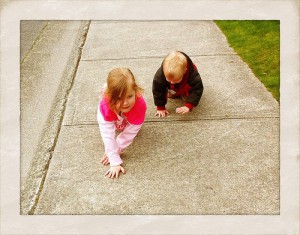

Am I that far off from the way a young child experiences life?

The next time our frustration starts to peak, let’s try to remember how new, complicated, fascinating and big this world seems through the eyes of our little ones.