“From overcrowded prisons, hospitals delivering staggering rates of babies whose mothers are addicted, to finding foster care shortfall solutions and public-school systems where I first heard phrases like, cradle to prison and school to prison pipeline. As a mother and grandmother, I wondered who are the children that are born with a predisposition heading them into prison?”

~ BeckyHaas.com

Becky Haas Interview with API for AP Month 2020:

Parenting with PEACE, Part 1 of 3

Trigger warning: this post contains brief mention of child abuse events in the fifth paragraph of Part 1.

API is pleased to interview Becky Haas as part of AP Month this year. Becky is an international presenter of trauma-informed care and the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) study, as well as a pioneer in successfully developing trauma-informed communities. Her seasoned presentation experience includes trips to Delaware presenting to state leadership at the invitation of their First Lady, as well as the training of multiple juvenile justice systems in both Virginia and Tennessee. She developed Trauma-Informed Policing training – now certified in two states for officer in-service credit – and has delivered it to the Oklahoma City Police Department, as well as precincts within Tennessee, North Carolina, Virginia, and West Virginia. She has worked in partnership with the Tennessee Association of Chiefs of Police (TACP) to make Trauma-Informed Policing Training available to officers statewide. Becky is a highly sought-out trainer for educators, often working directly with school superintendents. Together, they impact entire school districts on their journey to creating trauma-sensitive schools.

API is pleased to interview Becky Haas as part of AP Month this year. Becky is an international presenter of trauma-informed care and the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) study, as well as a pioneer in successfully developing trauma-informed communities. Her seasoned presentation experience includes trips to Delaware presenting to state leadership at the invitation of their First Lady, as well as the training of multiple juvenile justice systems in both Virginia and Tennessee. She developed Trauma-Informed Policing training – now certified in two states for officer in-service credit – and has delivered it to the Oklahoma City Police Department, as well as precincts within Tennessee, North Carolina, Virginia, and West Virginia. She has worked in partnership with the Tennessee Association of Chiefs of Police (TACP) to make Trauma-Informed Policing Training available to officers statewide. Becky is a highly sought-out trainer for educators, often working directly with school superintendents. Together, they impact entire school districts on their journey to creating trauma-sensitive schools.

When I heard about trauma-informed care, I was shocked at the brave people walking around among us, that so many people are trauma survivors.

Becky has served as the Trauma-Informed Administrator for a regional healthcare system, providing training development and delivery to healthcare staff in multiple hospitals, and she was instrumental in raising awareness of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) as a social determinant to poor health and addiction within rural Appalachia. Becky serves as a consultant to the East Tennessee State University/Ballad Health Strong Brain Institute and helped to pioneer the Northeast Tennessee ACEs Connection. Becky is married to Jonathan, and their greatest joys in life are their two sons and their growing families.

Becky, ACEs – adverse childhood experiences – have brought people together from many different fields, and I would like to hear about your background and what brought you to this work.

I’m actually trained in ministry, and for 24 years I worked in the church that I still attend. I was involved with recruiting volunteers, education programs, pastoral care, and visitation. I also taught law enforcement in 33 counties of Tennessee about car seat safety for six years through a grant-funded program at East Tennessee State University.

My prayer had been that whatever kind of work I could do, that it would just be something that made a difference for people. In 2012, that landed me working for the Johnson City Police Department, where I directed an $800,000 crime reduction grant to reduce drug related and violent crime. I had no criminal justice background, but I had to bring together a community coalition to address four strategies around that grant. It ended up being 19 programs that 35 agencies did together, and we won two national awards. We won the most prestigious criminal justice award of the year in 2014, Outstanding Criminal Justice Program of the Year for the Southern region. Maybe it helped coming into this role that I had no criminal justice background, as I wasn’t focused on “the way things are always done;” instead I brought a fresh approach to looking at all the causal factors of crime and how community partners could address them. During this time, I learned the value of the collective impact of bringing all voices to the table. We had public housing, city government, libraries, and corrections – that really made an impression on me. Here, I learned about ACEs in my journey at the police department.

Between hearing the two of them 30 days apart, I felt like I’d heard the cure for cancer.

One of the pillars of the grant was to create an intervention to reduce recidivism. I’ve lived in the community since the seventies, but I had not spent much time with the prison population or the judges who worked with the first judicial district felony offenders. They wanted to create the perimeter that the program would be for high-risk, high-need felony offenders with addictions. So, working with this population for years, I hear about ACEs in the second year of that, and I hear their stories of being raped by a parent, being raped by a relative, being held in a closet, I just wondered: why was ACEs not a part of the toolkit? Why was this education not widely known? When I heard about trauma-informed care, I was shocked at the brave people walking around among us, that so many people are trauma survivors.

And now ACEs and trauma-informed care are a part of many programs, largely because of your work. ACEs is being addressed in schools, hospitals, foster care, businesses, and of course law enforcement. What other audiences have you been working with and advising?

Before I told anyone what I was learning at the police department, I’d gone to two national conferences, and at one, Dr. [Vincent] Felitti spoke (Principal researcher of the ACEs study). Then I went to another, a probation conference in Florida where I heard Dr. Joan Gillece, who at the time was the Director of the National Center for Trauma Informed Care Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Between hearing the two of them 30 days apart, I felt like I’d heard the cure for cancer.

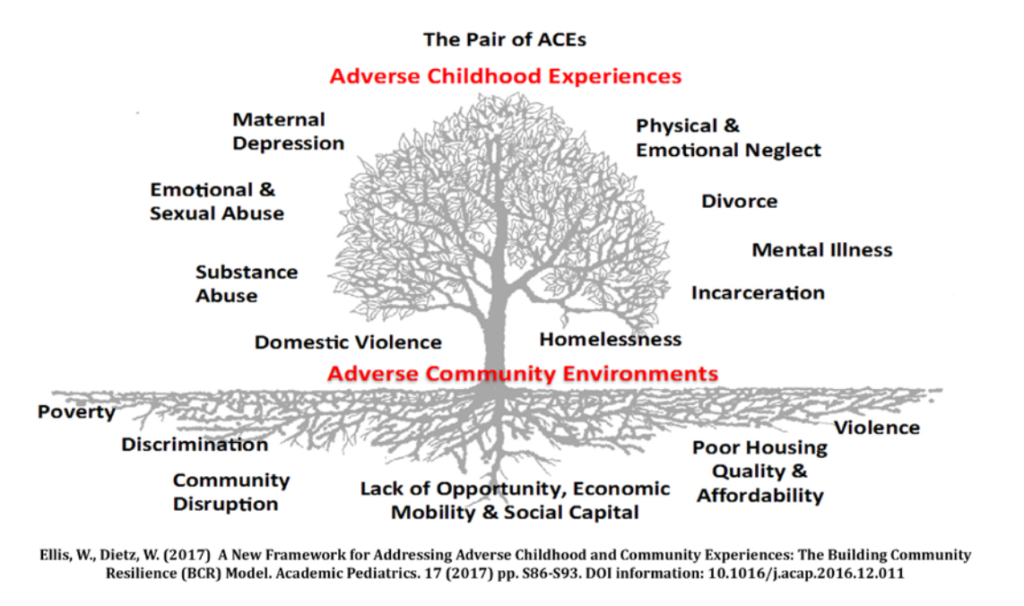

“What if I came back and didn’t tell my town?,” it struck me, as I almost felt now that I’d be held responsible if I didn’t. My first step was creating a huge binder, putting 35 tabs in it representing all the agencies who were helping me do crime prevention – the library, healthcare, housing authority, faith community, judges, etc. I then researched mostly using the global online learning collaborative, ACEs Connection, to see if there were meaningful applications for using a trauma lens in all those settings. I honestly didn’t know what I was going to find. I thought maybe it would apply to a few – but at the end, I could not close the notebook! When I found a program that was making a difference and having good outcomes, I printed it off, put it in the notebook. After a few months of research, every single tab — juvenile justice, schools — every single tab had an application for using a trauma-informed lens. So that convinced me that there was a need to bring this approach into every kind of service. Then I went over to East Tennessee State University (ETSU), and presented my findings to some department chairs to see who might help me educate the community. In 2014, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration (SAMHSA) at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services had published a concept paper that recommended reducing the effects of childhood trauma in a public health approach by way of community education of the cross sectors of professionals.

From that meeting at ETSU, Dr. Andi Clements emerged to help me. We never asked anyone if we could train them, but one by one, the group of partners I already had around the table every month for my policing program began to want training. In less than three years, we trained over 4,000 professionals while it wasn’t even in our job description nor did we have any funding to do it. I would get in the office at 6:00 in the morning to keep my 19 police programs running so that no one would ever feel that I took away from my job to do that.

In 2017, we wrote the National Center for Trauma Informed Care to ask if we could host a webinar in 2018 of all the cities that have been doing this kind of work. We wanted to learn from them. In response they said, “We don’t know of a city that has trained such a diverse group of professionals about trauma informed care in one community.” That was the first time we knew something special had happened in Johnson City. So, in 2018 we were asked to host a forum and tell our story. Attending the forum were two governors’ wives, people from 20 states, and leaders from SAMHSA. After hearing our story, they told us we had created a model that other cities should follow for how to create a trauma-informed community.

There’s a responsibility by the people who hear about it to do something with it.

In 2019 Dr. Clements and I wrote a toolkit, funded by the Tennessee Building Strong Brains Grant, on Building a Trauma Informed System of Care for the Tennessee Department of Children’s Services. In the summer, we received notification that an article on the toolkit we had submitted to Johns Hopkins was accepted to be published in their journal, Community Progress in Community Health, Research, Education, and Action in December. The toolkit has also been recommended in Growing Resilient Communities 2.1, through the global online collaborative ACEs Connection. It provides step-by-step information on how to advocate, educate, and collaborate to create a trauma-informed community.

The message you’re bringing communities, that you recognize as effective, is to advocate, collaborate, and educate. Can you describe how you want communities to advocate, educate and collaborate?

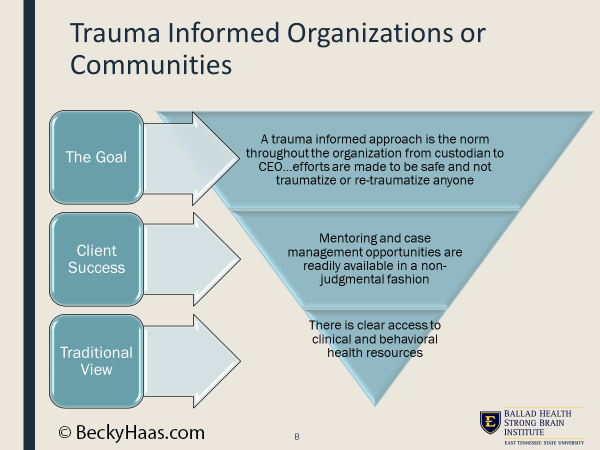

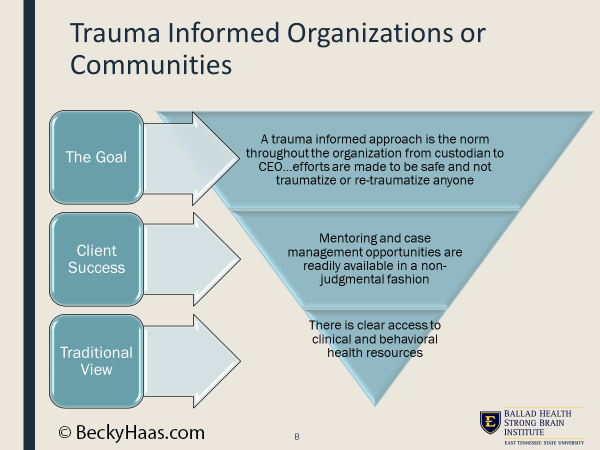

You take these three actions to raise awareness about the ACEs Study and how to build resilient communities. The SAMHSA course, which we’ve used to train thousands, describes a trauma-informed organization or community as those who:

- Realize the widespread impact of trauma and understand the potential paths of recovery.

- Recognize the signs and symptoms of trauma in clients, families, staff, and others involved in the system.

- Respond by fully integrating knowledge about trauma into policies, procedures, and practices.

- and seeks actively to Resist Re-traumatization. ~SAMHSA

There’s a responsibility by the people who hear about it to do something with it. In the SAMHSA training, there are six pillars: Safety, Trustworthiness & Transparency, Peer support, Collaboration & Mutuality, Empowerment & Choice, and Cultural, Historical & Gender issues. Dr. Clements and I framed it up as an inventory instead of just facts: Is your program safe? Do people feel safe there? Do they feel you’re trustworthy?

Now the work I’m doing is to bring this message to groups on a national level. Most recently, I’ve trained all the childcare leadership in the state of Mississippi and in Tennessee. I’m working with the Tennessee Association of Chiefs of Police to create a professionally recorded video training of my Trauma-Informed Policing training that will be made available to all members of law enforcement statewide.

I turned the pyramid upside down to explain the concept of resilience and hope. At the upper level, we infuse the community with empathy and understanding.

My hope is that by telling people what trauma is, and about its universal prevalence, we can create an environment that helps trauma survivors heal.

In understanding ACEs, the top of the coin is trauma and childhood household dysfunction, but on the bottom of the coin is resiliency. We’ve learned that resiliency can happen in the community. Resiliency can happen through a Boys and Girls Club, for example.

As communities learn about ACEs, I feel by using a trauma-informed lens to provide services, we could mitigate the effects of trauma, maybe by 50%. In the ACEs pyramid that came out of the original ACEs study, the base is childhood adversity, all the way to the top which is early death. In the training I deliver, I turn the pyramid upside down to explain the concept of resilience and hope. At the upper level, we infuse the community with empathy and understanding. The shop clerk who is very rude? Don’t take it personally. They may just have been served divorce papers, or failed a class at the university that they were barely affording anyway.

As communities learn about ACEs, I feel by using a trauma-informed lens to provide services, we could mitigate the effects of trauma, maybe by 50%. In the ACEs pyramid that came out of the original ACEs study, the base is childhood adversity, all the way to the top which is early death. In the training I deliver, I turn the pyramid upside down to explain the concept of resilience and hope. At the upper level, we infuse the community with empathy and understanding. The shop clerk who is very rude? Don’t take it personally. They may just have been served divorce papers, or failed a class at the university that they were barely affording anyway.

Then the middle layer is much more social work, much more navigating because many tasks we need to do in life are hard. But if your life is overwhelmed with trauma, you’re likely not going to do those things, because it’s too hard. It’s too complicated. The middle part of the model is more what I call “warm hand holding.” The bottom part is clinical interventions which are important, but not always essential.

I’ve heard story after story of people who healed, were helped, and were set on a good path by interacting with the upper and middle levels of the funnel. One recent story that I heard on the CBS news earlier this year, before COVID, is a favorite for illustrating the upper level. It’s about a bus driver in Utah, who loved driving the school bus. In this particular school year, she had a little girl getting on her bus, 11 years old, who she just struck up a friendship with. One thing she noticed about the little girl was how she always had her hair braided. A few months into the school year, one day, the little girl not on the bus. This expanded into a whole week missing. The next week on Monday, the bus driver was relieved to see the little girl back on the bus, but she noticed her hair was messed up and not braided. The driver reasoned to herself the little girl must have overslept. However, the next day the little girl got on the bus but again for several days her hair was not braided. Finally, the fourth day, the bus driver said to the little girl, “I sure miss those braids.” And the little girl said to her, “Last week, my mommy died and my daddy doesn’t know how to braid hair.” This touched the bus driver so much that after she dropped the children off at school, she went to Walmart to buy a clean hairbrush and a bag of bows. Every day after that, she began to brush and braid the little girl’s hair before she got off the bus and went into school. The teachers noticed that this single act brought that child in with a smile again, adding a little bit of a spark to her step.

It was so remarkable. They said something to the principal, who said something to the superintendent, and that story was on their local news. It made the national CBS news. That’s the top of the funnel of hope. In similar fashion, after training we now have librarians who realize youth coming in have not had anything to eat so they keep a snack drawer along with hygiene products. A local high school started a program called, “Suds for Buds” after students were trained about ACEs. They realized some of their classmates did not have access to these products at home so now they can clean up at school.

Can you see how this message is helping communities work the top and the middle part of the funnel to reduce the effects of adverse childhood experiences? There is a wonderful pilot program locally that is working to improve workforce sustainability by providing a navigator to the human resource departments of a couple of very large companies. As part of the employee benefits, they can access the navigator to find resources for things like paying their rent or purchasing a new set of tires without any blaming or shaming. This enables employees to stay on the job instead of struggling and quitting – actions which only contribute to a domino effect of complications.

Continue to Part 2 of 3

API is pleased to interview Becky Haas as part of AP Month this year. Becky is an international presenter of trauma-informed care and the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) study, as well as a pioneer in successfully developing trauma-informed communities. Her seasoned presentation experience includes trips to Delaware presenting to state leadership at the invitation of their First Lady, as well as the training of multiple juvenile justice systems in both Virginia and Tennessee. She developed Trauma-Informed Policing training – now certified in two states for officer in-service credit – and has delivered it to the Oklahoma City Police Department, as well as precincts within Tennessee, North Carolina, Virginia, and West Virginia. She has worked in partnership with the Tennessee Association of Chiefs of Police (TACP) to make Trauma-Informed Policing Training available to officers statewide. Becky is a highly sought-out trainer for educators, often working directly with school superintendents. Together, they impact entire school districts on their journey to creating trauma-sensitive schools.

API is pleased to interview Becky Haas as part of AP Month this year. Becky is an international presenter of trauma-informed care and the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) study, as well as a pioneer in successfully developing trauma-informed communities. Her seasoned presentation experience includes trips to Delaware presenting to state leadership at the invitation of their First Lady, as well as the training of multiple juvenile justice systems in both Virginia and Tennessee. She developed Trauma-Informed Policing training – now certified in two states for officer in-service credit – and has delivered it to the Oklahoma City Police Department, as well as precincts within Tennessee, North Carolina, Virginia, and West Virginia. She has worked in partnership with the Tennessee Association of Chiefs of Police (TACP) to make Trauma-Informed Policing Training available to officers statewide. Becky is a highly sought-out trainer for educators, often working directly with school superintendents. Together, they impact entire school districts on their journey to creating trauma-sensitive schools. As communities learn about ACEs, I feel by using a trauma-informed lens to provide services, we could mitigate the effects of trauma, maybe by 50%. In the ACEs pyramid that came out of the original ACEs study, the base is childhood adversity, all the way to the top which is early death. In the training I deliver, I turn the pyramid upside down to explain the concept of resilience and hope. At the upper level, we infuse the community with empathy and understanding. The shop clerk who is very rude? Don’t take it personally. They may just have been served divorce papers, or failed a class at the university that they were barely affording anyway.

As communities learn about ACEs, I feel by using a trauma-informed lens to provide services, we could mitigate the effects of trauma, maybe by 50%. In the ACEs pyramid that came out of the original ACEs study, the base is childhood adversity, all the way to the top which is early death. In the training I deliver, I turn the pyramid upside down to explain the concept of resilience and hope. At the upper level, we infuse the community with empathy and understanding. The shop clerk who is very rude? Don’t take it personally. They may just have been served divorce papers, or failed a class at the university that they were barely affording anyway.