Becky Haas Interview with API for AP Month 2020:

Parenting with PEACE, Part 2 of 3

In our work, Becky, we have parenting leaders and educators in local communities. We’re also training, and we’re helping them deal with preconceived ideas about parenting, preparing them to facilitate group meetings – to love, accept, welcome, and help caregivers with their parenting. We support those whose stress is affecting their coping and creativity as parents. We wrap this in the API Principles that are very foundational and grounded in research. We’re doing a lot of your infusing the community with empathy, understanding, and warm handholding.

As ACEs awareness is integral to understanding resilience, what childhood environments are more likely to predispose people to grow up without developing a high level of resilience?

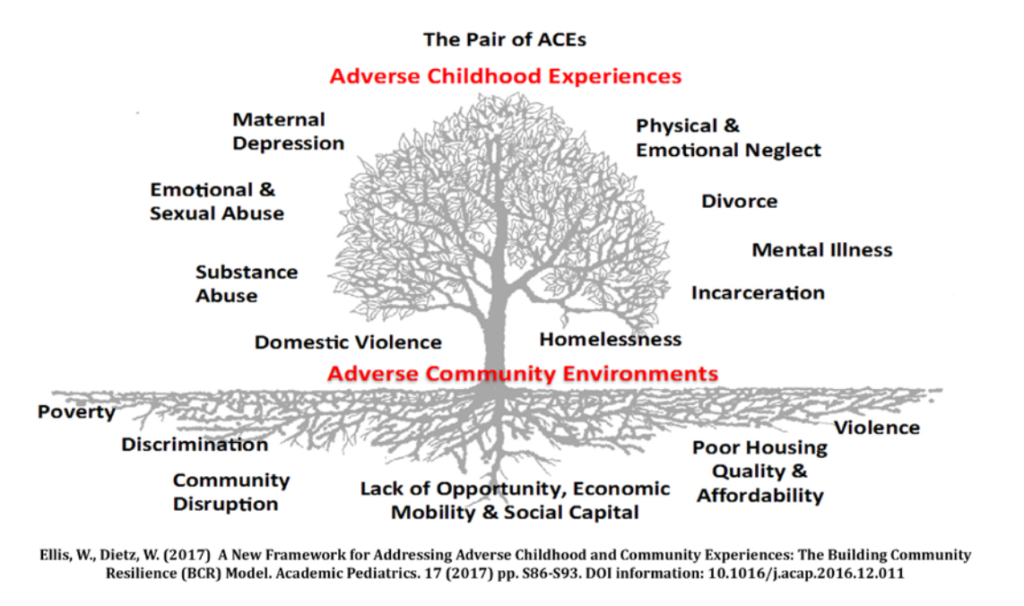

The Milken Institute of The George Washington University School of Public Health’s Dr. Wendy Ellis and some of her team developed a graphic called the Pair of ACEs. With that graphic, they show that poor soil creates poor fruit on the tree. The soil illustrates the challenges like lack of affordable housing, food scarcity, and lack of employment. A tree growing in this soil is then likely to grow the fruit of domestic violence, drug addictions, or an incarcerated parent.

Referring again to the funnel of hope, some schools locally, for instance, have hired a social worker through a nonprofit called Community in Schools. That social worker gets referrals from the teachers or the principal for families that might be struggling with housing or medical needs. I was surprised to learn when I worked at the police department, our city schools reported every year they had 300 to 400 kids classified as homeless. That didn’t mean many of them lived under a bridge or slept in a car, but it meant when they left the classroom every day, the teachers did not know where they could be found. They had no permanent address. But as we understand trauma-informed care, providing a social worker in the school can help address needs that students and their families are facing outside of school.

Statistically, it takes seven acts of violence before someone will reach out to an advocate. That means there is a lot of unreported violence children are witnessing in their homes.

We can see that ACEs occur from the wealthiest parts of town to the most difficult parts. Domestic violence is not socioeconomic; there is no barrier there. In 2015, in my zip code, we averaged nine calls a day that were coded domestic violence. Statistically, it takes seven acts of violence before someone will reach out to an advocate. That means there is a lot of unreported violence children are witnessing in their homes. This is what gave me the idea to train police. Police are likely called to the home and they can provide a small intervention to children who are present to help reduce the trauma. When police are trained in trauma-informed policing, they step in and they say to the child, “You did the right thing. If you feel unsafe, you call us.” Training also directs the role of police in communities as a guardian instead of a force.

ACEs inventories identify people at high risk, but you also talk about “universal precautions,” keeping a trauma-informed lens based in the 70% statistic of those around us.

Since 2014, as an ACEs educator, I have always presented the national statistics on violence. There are 65% of women in substance abuse treatment who report histories of trauma, 75% of men treated for drugs have a history of trauma, 92% of homeless women have histories of trauma. In 2013, the American Journal of Public Health said homeless individuals have the highest ACEs scores of any population. When I give an ACEs education presentation, we talk about the ACEs test itself, but I’ve never even recommended a group to screen for ACEs. Not that I would be opposed to it, but I feel that if you screen, then you just need to make sure you have services to connect someone once you see what the score reveals. I strongly recommend the universal precautions method because those numbers I’ve cited pretty much tell us that of all the staff we hire, as well as all the consumers we serve, for instance, almost 70% are trauma survivors in some form or fashion.

What if 70% of the people you serve are trauma survivors – then how welcoming are you?

Some have had much more trauma and no healthy support, even among our staff. I do a training where professionals that were in my training, email me, or send me a chat in the chat box of their own story of some abuse and neglect that they’ve overcome. So, I did some work. Back two summers ago, I spoke at the Senator Tommy Burke’s Victims Academy, which is a statewide victim advocate academy that’s held every summer. They asked me to speak about why we need to have trauma informed multidisciplinary teams as best practice. The reasoning that I gave was if you knew that 70% of your services were going to go to people who were hearing impaired, how would you prepare? You would have videos with closed captioning. You would have people who knew sign language. What if 70% of those you serve, were going to face mobility challenges? Federal guidelines say we need to have handicap ramps and handicap accessibility and restrooms. What if 70% of the people you serve are trauma survivors – then how welcoming are you? How can we ensure our services are not re-traumatizing consumers? That, to me, is when you accept a universal precautions approach.

There are several trauma-informed descriptors – aware, sensitive, responsive. Can you talk about what those are at the individual and societal levels?

Often, I’m asked to conduct training on the Missouri Model. In the national work I do it’s pretty much recognized as a best practice. It has a paradigm that starts with trauma-aware, then it goes to trauma-sensitive and trauma-responsive, then to trauma-informed. Sitting through a two- or three-hour training does not make someone trauma-informed. This is a journey. If you compare this to tobacco use, we have seen it go over several decades from a popular fad in culture to now being banned from most public properties. How to transform the culture of an organization is addressed by the Missouri Model; in a three-hour workshop, I can help leadership create an action plan for how to change the culture of an organization to become trauma-informed.

I feel like this field found you, shifting culture toward empathy and understanding that is deep and sustainable; you have a gift for helping people understand trauma and how to be sensitive. Like many, I felt very inspired after I was trained by you. When you train, you tell a lot of stories and your approach with these stories is very engaging. You collect stories. Can you share why and how your service and story collecting started?

My parents—I’m one of five children—they were very community based. They would have the college kids who sold the encyclopedias in summertime start living in our house and having dinner. As a matter of fact, one year they told us that their supervisor said, “Don’t go down to that neighborhood, because you’ll want to quit. This little family is going to take you in.” I’ve spent nights in a chicken coop with Vista workers up in Princeville, Tennessee. That’s my childhood. That’s how I grew up. I think some of that made this resonate with me, and I’m always very fascinated by people’s stories.

When I heard about ACEs, it was the first time I felt I could help people with faith, encouragement, prayer, and compassion.

Collecting stories goes back to my days in ministry. I’ve often pondered how did I get picked to do this? Certainly, faith is integral in my life. When I worked in ministry, I would be sitting up in ICU holding the hand of a 70-year-old gentleman whose wife had congestive heart failure and they’ve called the family. The family lives around the world, and I’m sitting there with them that night, while he’s hearing these conversations with medical people about the hours that his wife has left to live. I see those tears falling down his cheeks, and it’s a sacred place to be there with someone.

I’ve wondered, do I like have this sign over my head – if you’re in the worst day of your life, call Becky. I’ve never forgotten a story of human suffering and human resilience. Before I knew about ACEs, it stuck to me like lint on a pair of black slacks. I felt people were such heroes. One of my dearest friends, who’s in his nineties now, when he was a little boy his father went to the doctor and never came home. His father died of tuberculosis. His mother went away sick, and he was so worried as a little boy; lo and behold, she also died of tuberculosis. He told me that he and his two sisters went to live with an aunt and an uncle. Every Sunday after church they’d get dressed up for church. They would sit in the parlor, and they noticed an unusual number of people would come by. One day it dawned on him that the aunt and uncle were trying them out to see if someone might adopt them. I’m hearing all these stories, and I don’t always know what to do with them. When I heard about ACEs, it was the first time I felt I could help people with faith, encouragement, prayer, and compassion.

With ACEs, how could we protect a child?

ACEs gave me a meaningful way, on a big scale, to raise awareness to the courage of people around us. How the smallest of kindnesses brought some comfort: sitting in intensive care or going to visit someone whose young person is suddenly in jail. ACEs has given me a way to really raise awareness of how much kindness means to people when they’re in suffering. I don’t know if I found ACEs, or ACEs found me.

We know that higher ACEs scores are associated with so many things, alcoholism, depression, health issues, employee absenteeism, job performance, and more. It’s significant on the individual level, of course, but what do you see that it does to a community?

I didn’t realize until working for police the trickledown effect of the drug epidemic. Now that we know about ACEs, it’s almost like which came first, the chicken or the egg. The drugs are not ACEs, and trauma is not an excuse for drugs and crime – but now it offers us an explanation. We know that when bad things happen to people, they have to cope. You and I have found healthy coping mechanisms where some people turn to risky behaviors at an early age: tobacco, underage drinking, drug use, cutting, and eating disorders. I saw the impact that addiction had on the community. When I was overseeing the prison program what we were doing about this was being replicating across the state.

Instead of kicking them out, we hold them more tightly, you know, and what was that going to look like over time.

As we learned about it, a restaurant owner would call me and say I appreciate the work you’re doing. I have a child that’s been in and out of rehab. The next time you all have a gathering, I want to cater that event and do it for free. I was amazed at how many people were touched in the community. Then I saw the numbers. I sat in city commission meetings, hearing local government leaders in a local county. The sheriff told me that in 2010, it cost about $650,000 to run the jail for a year. And then in 2018 or 2019, it jumped to $2.9 million! I saw government leaders talking about how to fund our hospitals, how to dedicate more floors to deal with the volume of babies being born addicted.

That was another reason I championed this message, because it provided this upstream approach, instead of trying to deal with everything through more jails. In 2014, a study done by the Pew Charitable Trust compared Tennessee to New Jersey. Tennessee is the fifth highest state for using incarceration to monitor drug crimes, while New Jersey is 45th. Yet our drug rates and drug crimes continue to grow at the same rate. The summary of that report was incarceration is not reducing drug crimes. I didn’t know anything about this. I sat in city commission meetings and heard mayors talk about this. I heard police chiefs talk about it, how costly, at $80 a day in Tennessee, to incarcerate someone for one night. You have to assume all the healthcare, you have to assume the dental, the clothing, the laundry. That’s the reason that the county jail, if you have one person incarcerated that has HIV or Hep C, the medical treatments for that are amazingly expensive.

I saw what the drug epidemic was doing to the community and how costly it was affecting us all with taxes to staff and build. But yet, I didn’t see anyone saying conclusively, that if we keep going this way, we’re going to eventually end it. With ACEs, how could we protect a child? When I did work in healthcare, we had 50 school districts in our healthcare footprint. What if we had 50 trauma-sensitive school districts, how many more kids would, over 10 years, 15 years, affect the health of a region? If a lot of that was mitigated in a school setting, teachers who were trained in college to deal with “willful” behavior all of a sudden were trained now to know it as survival behavior. Instead of kicking them out, we hold them more tightly, you know, and what was that going to look like over time.

It definitely impacts the community.

One thought on “Learning More about ACEs and Fostering Positive Childhood Experiences with Becky Haas: Part 2 of 3”